|

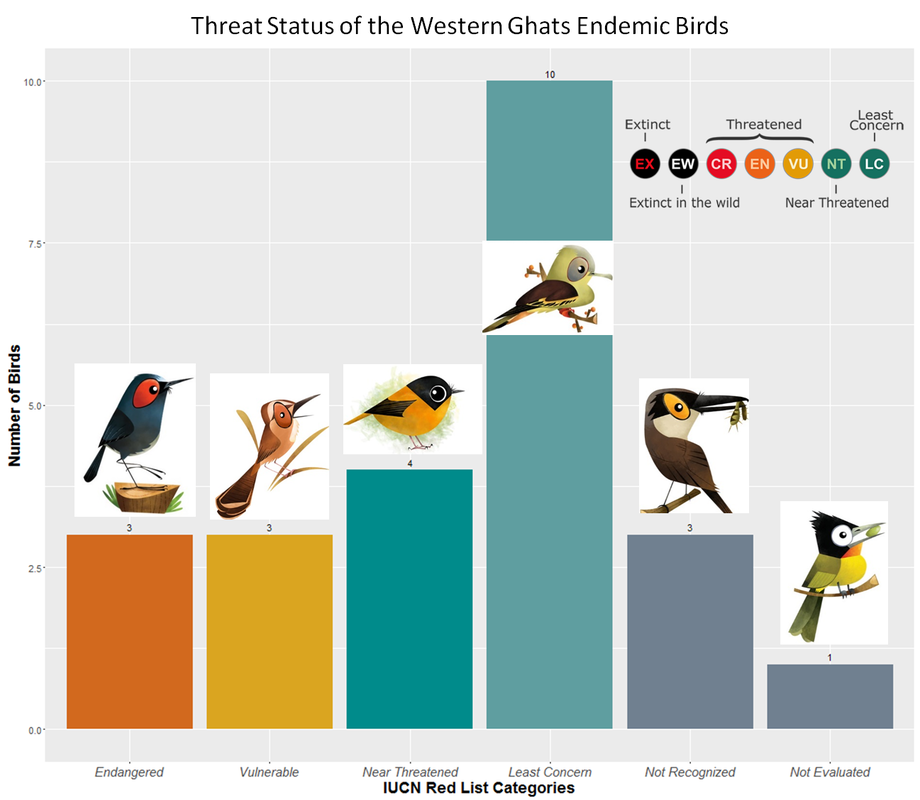

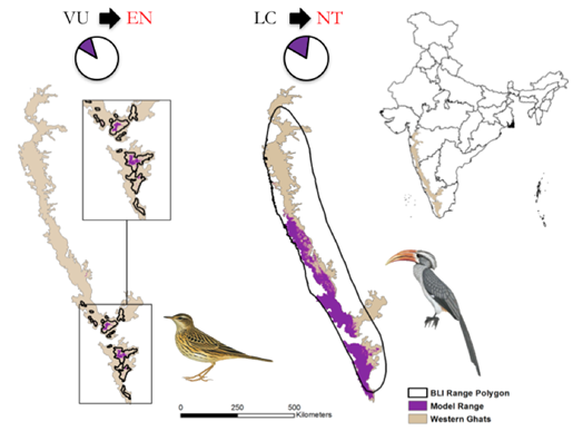

Many species of birds in the Western Ghats have exclusively adapted to inhabit isolated pockets of this region and are found nowhere else in the world. These species are threatened as a result of widespread development and are in need of protection. However, their survival is currently being undermined by inaccurate range maps which quantify the size of species’ geographic spread and are a key determinant used by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to assign an appropriate threat status. Using information collected from eBird - the world’s largest citizen science database - along with freely available data on land cover, climate, and vegetation, I worked with a team of scientists to assess the accuracy of ranges used by the IUCN for 18 endemic bird species in the Western Ghats. We found that for 17 of these species, the range maps grossly overestimate the area that the birds actually inhabit. This investigation began when Dr. Sahas Barve of Old Dominion University, a researcher on this study, looked up the distribution of the Nilgiri flycatcher (listed as ‘Near Threatened’ by the IUCN), an endemic species found in the Western Ghats. After a disappointing search for information, he realized that accurate range descriptions for many birds endemic to the Western Ghats are noticeably absent from scientific literature. Sahas Barve and Trisha Gopalakrishna in the Western Ghats of Southern India In search of an explanation for this gap, we contacted BirdLife International (henceforth BLI), the ‘red-listing’ authority for birds - and procured range maps for birds all over the world. We visualized the purported range of the Nilgiri flycatcher using GoogleEarth and found extensive agricultural plantations, townships, and development projects within areas demarcated by BLI as suitable habitat for the species. This raises both a red flag and a question: What information did BLI use to create these maps, which clearly include unsuitable habitat? A former employee of the IUCN told us that many of BLI’s range maps are actually hand-drawn by an expert for each species. The potential for imprecision in this approach, along with its lack of data-driven rigor, is deeply unsettling. These maps are used to officially classify species’ threat status – designations which managers and policymakers use to guide development projects which could potentially destroy essential habitat on which endemic species rely. Citizen science has gained tremendous popularity in India, which is one of largest contributors of data to eBird - an online bird-spotting ‘checklist’ program which allows users to record bird sightings at any location. On the ground - deep in the forests of the Western Ghats - a million citizen scientists have been using eBird on their phones, laptops, and tablets to document the locations of bird sightings. These records are continually added to an extensive archive that dates as far back as the early 80s, for certain species. The map on the right shows commonly bird(ed) locations along with endemic bird areas (EBAs) across India (Image courtesy: eBird) Trisha Gopalakrishna from Duke University, a key contributor to the study, suggested that we employ an up-and-coming approach known as ‘species distribution modeling’ to create our own – more accurate – range maps, to compare to the BLI maps. This method produces a robust distribution model by estimating the relationship between the known location of a species and the environmental conditions that are characteristic of that location. Using data on temperature and precipitation, along with high-resolution maps of forest and land cover in the areas where species have been observed, we can identify locations with similar environmental traits to those where the species have not been reported. We built range models for 18 species of birds from the Western Ghats with habitat requirements ranging from forests to tea plantations. When we compared these models to ranges used by the IUCN, the size discrepancy was stunning. The present Threat Status assigned by the IUCN for some of the Western Ghats endemics are show above (Representative images of birds for each threat category were obtained from www.greenhumour.com; Please note above images are for Non-Commerical Use only. Write to Rohan Chakravarty for permissions) Of the 18 species in our study, 17 of these birds’ ranges are severely overestimated by BLI. Moreover, we found that half of these species are not actually found in over 60% of the areas mapped by BLI. For instance, the Nilgiri pipit, which is currently listed as ‘Vulnerable’ by the IUCN, has a range of less than 1,392 km2, whereas BLI lists its range as 11,558 km2, thereby overestimating the range by a staggering 88%. This makes the species appear artificially robust and as a result, it is not afforded appropriate protections. Our models also revealed that suitable habitat for many species exists outside the range drawn by BLI. Threatened species could potentially inhabit these areas if forced out of their existing habitat. If these areas are not protected, they too could be decimated by development projects – eliminating a potential haven for displaced bird populations. Range maps have been overestimated by BLI and NatureServe for both high elevation specialists such as the Nilgiri pipit (Anthus nilghiriensis) shown on the left to low elevation species such as the Malabar grey hornbill (Ocyceros griseus) shown on the right. The black outline represents the range polygon used by IUCN for threat assessment and the range in purple represents the range modeled in this study. The dust brown color represents the boundary of the Western Ghats. Moving forward, conservation planners must take into account areas where endemic birds are known to exist, as well as areas that could serve as potential habitat, and strategize their projects to avoid these high-value conservation areas. Today, as citizen scientists attempt to observe the Nilgiri flycatcher in field, they will soon realize that this species is no longer on the brink of threat, but is in fact vulnerable to imminent decline if conservation action is not taken. With an ever-increasing number of development projects in the Western Ghats, the Nilgiri flycatcher’s situation is sadly not unique. To prevent what would be a devastating loss to the biodiversity of the Western Ghats, we issue the following calls to action:

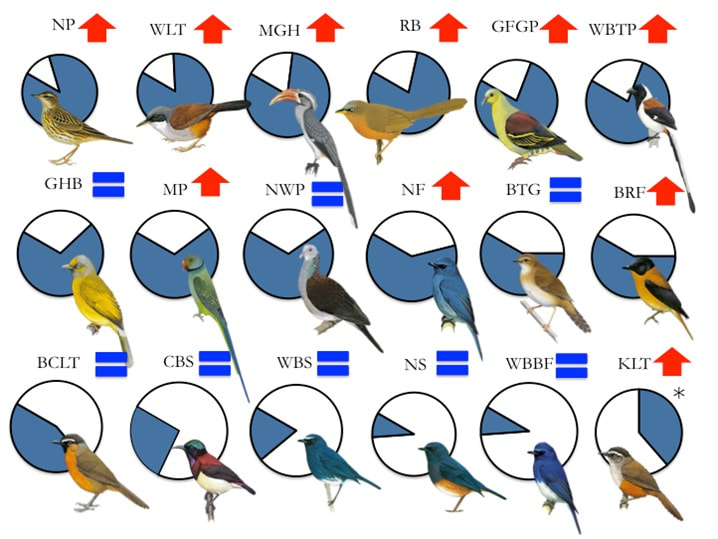

While the environmental impacts of extensive deforestation, compounded by the intensifying effects of climate change, paint a bleak picture for the endemic birds of the Western Ghats, appropriate management – if implemented swiftly – could save these magnificent species. Range overestimation for 18 species of Western Ghats endemic birds. White portion of pie chart shows percent suitable habitat within IUCN range, blue portion shows percent of the range where unsuitable or no habitats are predicted. Red arrows indicate species with potential need for IUCN threat status uplisting. Blue ‘equal’ signs indicate species where no uplisting is currently needed. Asterisk for Kerala Laughingthrush (KLT) indicates that it is estimated to be found in an area larger than current BLI range maps. Acronyms used: NP = Nilgiri pipit, WLT = Wynaad laughingthrush, MGH = Malabar grey hornbill, RB = Rufous babbler, GFGP= Grey-fronted green pigeon, WBTP = White-bellied treepie, GHB = Grey-headed bulbul, MP = Malabar parakeet, NWP = Nilgiri wood pigeon, NF = Nilgiri flycatcher, BTG = Broad-tailed grassbird, BRF = Black-and-orange flycatcher, BCLT = Black-chinned laughingthrush, CBS = Crimson-backed sunbird, WBS = White-bellied shortwing, NS = Nilgiri shortwing, WBBF = White-bellied blue flycatcher, KLT = Kerala laughingthrush This study was published online in the journal Biological Conservation.

1 Comment

12/21/2023 02:40:50 pm

Website source:

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAvid reader, conservationist, quizzer. Archives

April 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed