|

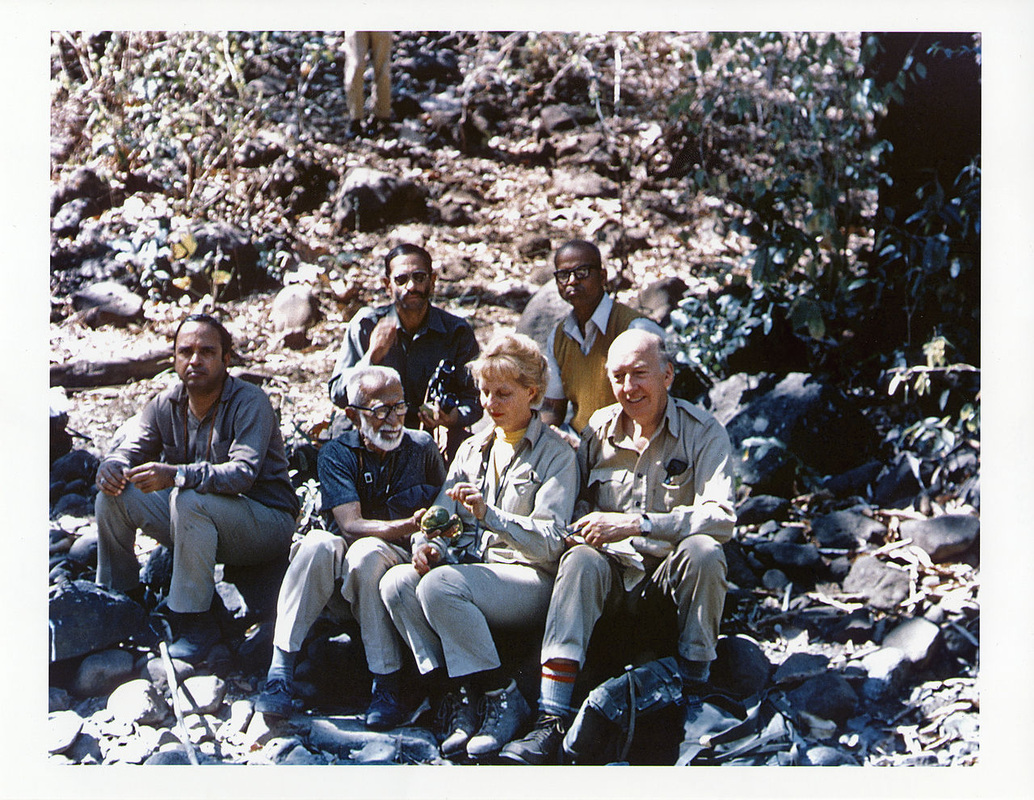

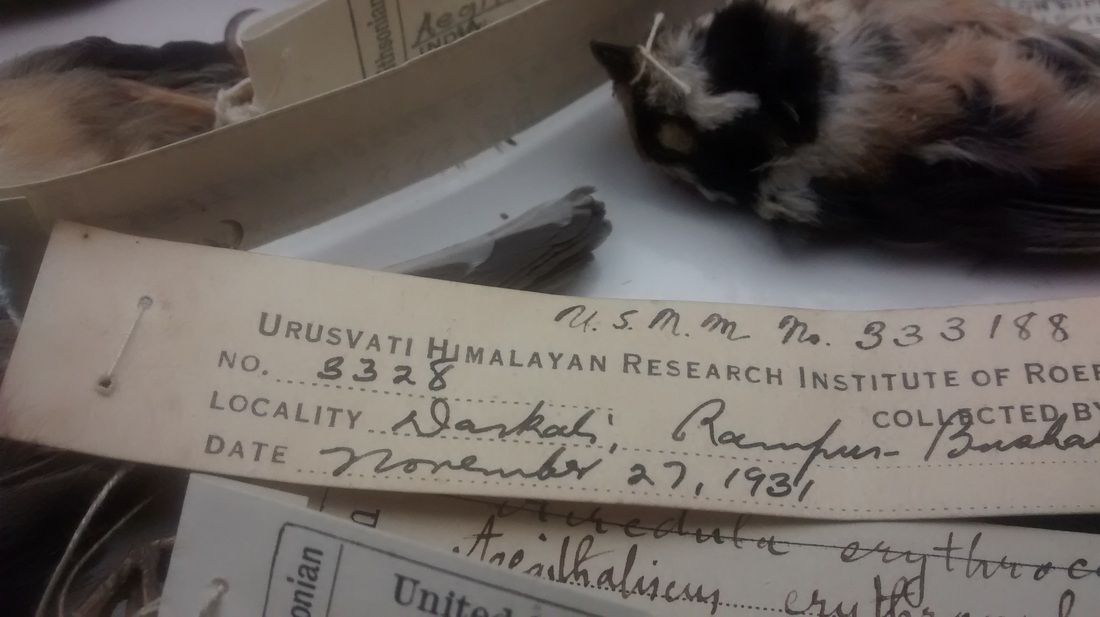

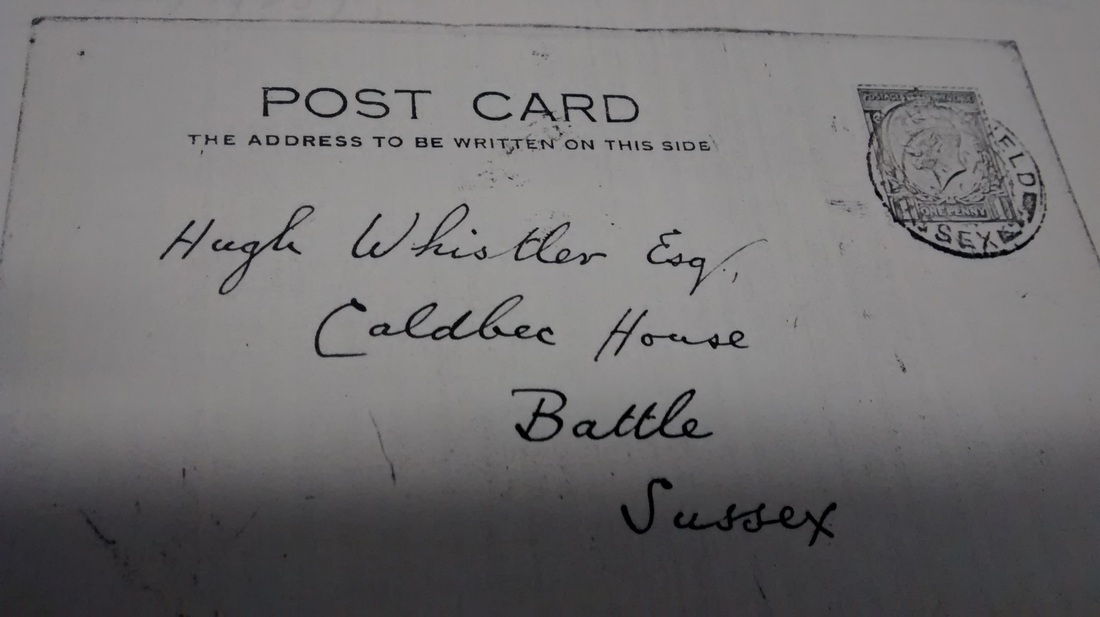

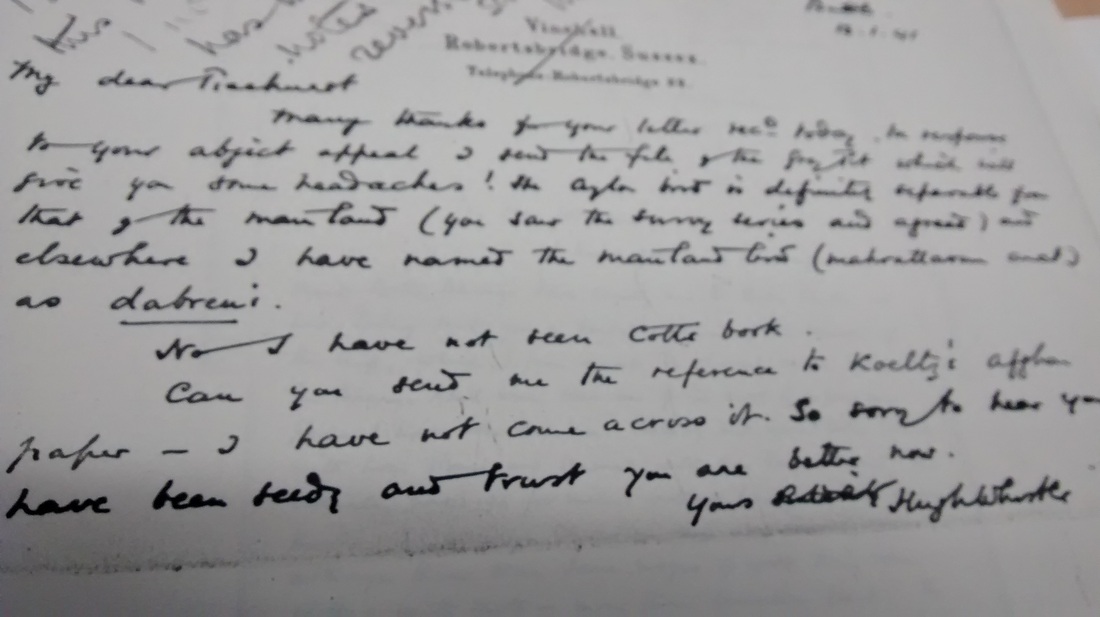

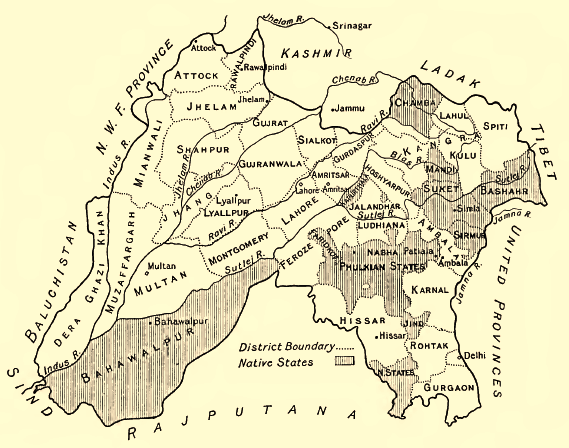

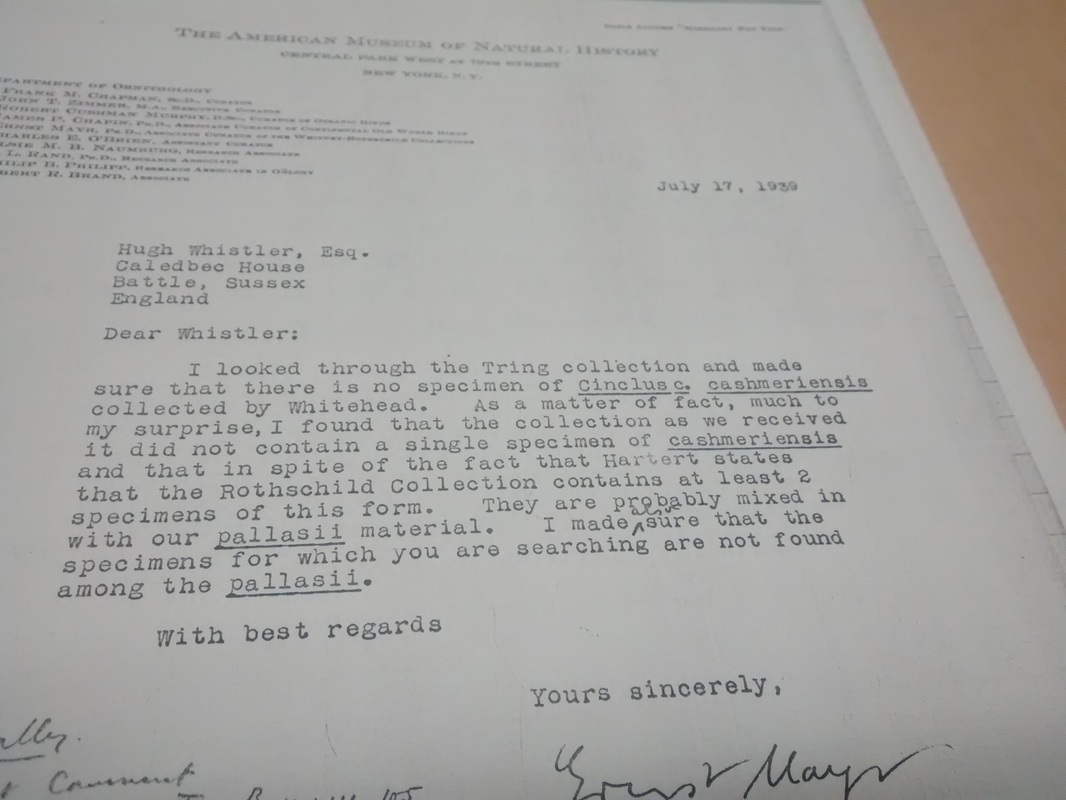

It was a wintry cold day in Washington. The Smithsonian Metro Station was really clean compared to its counterparts in the Big Apple. I had travelled down here from Columbia University over my winter break to start my thesis work on birds half a world away. The first thing I spotted as I got off the Metro was the Washington Monument, which was built to commemorate the first American president. With two bags by my side, I first walked to the National Museum of Natural History. There, I was greeted by Brian Schmidt and Dr. Gary Graves (Collections In-charge and Curator of Birds respectively), who took me to the 6th Floor at the Museum where all the birds are located. The bird collections at the Smithsonian Institution are the 3rd largest inventory of birds in the world. I was here to look at the bird collections from the Western Himalayas, particularly those of the former secretary of the Smithsonian Institution S. Dillion Ripley, an ornithologist and a conservationist who was a keen enthusiast of Indian avifauna. He and Salim Ali, published one of the most detailed notes on the birds of India (A ten volume magnum opus titled ‘Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan’). Ripley’s ornithological interests in India started at the age of 13, when he visited Ladakh and Tibet which pushed him to pursue Zoology at the very building I am doing my Master’s course in Conservation Biology now. His lifelong collaboration with Salim Ali started in the late 40’s when they started corresponding with each other about Indian avifauna. In fact, Ripley entered Nepal pretending to be a close confidante of the then Prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru. When Nehru realized this, he became furious and almost refused Ripley any more access to specimens in India. One of the entrances to the National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC However, Ripley did come to India in 1976 and shown below is a picture taken with his wife, Mary Livingston and Salim Ali (Courtesy of Wikipedia). It was 11 30 in the morning and I decided that it was time to get started. I started by pulling out specimens from the Western Himalayas which included Great Tits, Green-Backed Tits, Himalayan Bluetails and White-Throated Laughingthrushes. As a graduate student with interests in historical ecology, I started taking detailed notes regarding the origins of each specimen and came across a few names often, such as Walter Koelz and Jon Jantzen, with specimens dating back to the 1931 expedition. Koelz was a phenomenal explorer who has single handedly contributed to majority of the bird collections from the Eastern Himalayas. Most of these birds currently sit at the University of Michigan’s Museum of Zoology. In today’s governmental setup in India, it is almost close to impossible to collect avian specimens for research and even if one does obtain permits, very few people are being trained in the art of skinning and preserving birds in India. Dr. Walter Koelz , a PhD in Zoology first came to India when he was offered a position at the Himalayan Research Institute of the Roerich Museum in 1930. My work desk at the National Museum of Natural History, along with specimens of the Cinereous Tit (Parus major cinereus) As I found specimens tagged with the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute of Roerich Museum, I began to wonder where it exactly was since I had never heard of a museum such as this in India. Specimens with the Urusvati Tag As I searched on google for information regarding the institute, I came across this interesting webpage, which describes its entire history. In fact, the famed painter Nicholas Roerich and his wife Helena set up this international institute as a means to promote and encourage traditional science. I encourage you to check this nice little piece- http://en.icr.su/evolution/urusvati/ The second day in Washington was no different that the first in terms of the weather. I proceeded to reach the Smithsonian Institution archives today as I wanted to find out more about how Ripley and Salim Ali went about in preparing their magnum opus. Two months before I boarded a bus to Washington, I had met Dr. Pamela Rasmussen at the American Museum of Natural History, where I currently work as a graduate student researcher, who had mentioned that a British police officer and ornithologist by the name of Hugh Whistler had kept detailed accounts of all his observations when he was part of the Punjab Police between 1920 and 1924. The Smithsonian archives are not located in the same building as the National Museum of Natural History and is right by the L’Enfant Plaza Metro Station. I was greeted by Mr. Tad Bennicoff as I entered the archives and I got myself a badge, left my bag in a locker and carried my laptop and a few pencils into the reading room. I heard a creaking noise down the corridor. 9 boxes of manuscripts and materials collected by Ripley were being rolled down in a trolley for my reference. The next 4 days were spent here as I unearthed chunks of ornithological gold. Wearing gloves and carefully browsing through handwritten observations regarding the exact location, number and species of birds found in hotspots such as the Himalayas and the Western Ghats, I realized that Hugh Whistler was one of the greatest ornithologists and naturalists to have ever worked in the Indian subcontinent. Son of a painter, he served in the Indian police and was mostly stationed at Punjab. He was in fact in India from 1909 until 1926. During this period, he was meticulous in making detailed observations regarding the behaviour, location and the number of birds across various seasons. He wrote extensively in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society and journals such as Ibis. Until the early 1930s, the focus in Indian ornithology had been mostly collection based rather than observation based. Although Whistler himself contributed over 17,000 specimens to the British Museum, he recognized the need to observe the bird in its natural habitat and thus he writes: “The day is now over in which it was necessary to collect large series of skins and eggs in India. Enough general collecting has been done; concentration on filling in the gaps in our knowledge is now needed. Those who wish to help in the work should first familiarise themselves with what has been accomplished and learn what remains to be done. With some species the distribution of the different races still needs to be worked out and this implies careful collecting in certain areas. Of other species we still need to know the plumage changes; for this specimens collected at certain times of the year are required. In other species the down and juvenile plumages are unknown. But the greatest need of all is accurate observations on status and migration. In this all can help. Keep full notes for a year on the birds of your station, noting those that are resident and the times of arrival and departure, comparative abundance and scarcity of all the migratory kinds; and you will have made a contribution to ornithology that will in the measure of its accuracy and fullness be a help to every other worker” (Source: Popular Handbook of Indian Birds) Source: Smithsonian Archives Exchanges between Hugh Whistler and another famed ornithologist of that time, Claude Ticehurst (Source: Smithsonian Archives) Claude Ticehurst was a famed ornithologist and was a great friend of Hugh Whistler. They met when the former was stationed at Karachi and his short visits to Quetta and Besra led to a life long friendship, before Claude passed away in 1941. As I read through some of Whistler's observations, I noticed the amount of detail and meticulousness of his records. His records were most impressive for the Kangra district (Formerly part of the Punjab provinces, and now located in the state of Himachal Pradesh), as he maintained detailed observations from 1920 -1924 all over the entire district. A 1911 map showing Kangra (Source: Wikipedia) Further, as I went through more of Ripley’s collections of Whistler’s manuscripts, I noticed correspondences between Whistler and Ernst Mayr, then curator of the American Museum of Natural History suggesting the extent Whistler went to so that he could verify his records and later publish his findings in the Popular Handbook of Indian Birds (1928). Source: Smithsonian Archives Some of the correspondences between Whistler and Ticehurst suggest that a detailed book on the distributions of all birds of the Indian subcontinent were planned, but they passed away before their efforts could come to fruition. But, Ripley and Ali ensured that their efforts did not go to waste and incorporated many of their observations in their magnum opus (Handbook of the Birds of India & Pakistan). The next few days were enriching not just in terms of the data I was able to obtain, but on the personal front as I learnt how important it is to keep detailed notes in field.

In conclusion, I would like to thank Brian Schmidt, Tad Bennicoff, Sudharshan Aji (For a wonderful place to stay and taking me around Washington!, Soda, you are awesome) and professors and colleagues at Columbia University who encouraged me to go find the ‘hidden treasure’.

47 Comments

|

AuthorAvid reader, conservationist, quizzer. Archives

April 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed